The enduring romance of the Morris & Co. archive

The enduring romance of the Morris & Co. archive

Not far outside of London, just off the A40 in Denham, sits a humdrum brick building with dropped ceilings and halogen lighting, and packed lunches in the fridges like other offices. The exterior is forgettable. If you were in the car on the way to the Chilterns, and glanced over your shoulder during the quarter-second it was slipping past the window, the red and white facade wouldn’t register on your inner eye. This is the doorstep of one of the most influential strongholds of British heritage design. In temperature-controlled rooms, there are fabrics, wallpapers, production notes and printing materials, all stored in slim steel drawers, which have enchanted people in three centuries. Here is the modern home of the Morris & Co. archive.

It’s impossible not to wonder what William Morris, the 19th century’s best-known aesthete, would have made of this practical setting. Morris launched his decorative company in 1861 in opposition to the ugliness of Victorian mass production, which churned out machine age homewares to sell to the flourishing middle class. These newly empowered customers had houses to decorate and money to spend, and Morris believed they should be offered products that were, simply put, more beautiful and of higher quality. He felt that the makers of these objects should have a stronger connection to their work than one stroke on an assembly line.

Morris employed the antiquated, small-scale production method of block printing to produce his patterns, using pearwood blocks cut by Barrett’s of Bethnal Green, some of which are in the archive in Denham. He rejected the synthetic aniline dyes that had become popular at the time (referring to these as ‘the foul blotches of the capitalist dyer’) in favour of more fickle natural dyes, and spent years perfecting the application of colour. For the content of his designs, he looked to nature: to old-fashioned English garden flowers like dog roses, larkspur and honeysuckle, daisies in meadows and hawthorn hedgerows. Morris kept a copy of John Gerard’s The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, published in 1597 with useful close-up illustrations, at his elbow as a reference.

The most famous pattern Morris produced, Strawberry Thief, in 1883, was inspired by the birds in his garden at Kelmscott Manor in the Cotswolds. His daughter May Morris said about the chintz: ‘You can picture my Father going out in the early morning and watching the rascally thrushes at work on the fruit-beds and telling the gardener who growls, “I’d like to wring their necks!” that no bird in the garden must be touched. There were certainly more birds than strawberries in spite of attempts at protection.’

Victorian consumers were captivated by Morris’s vision. His commercial and artistic success put wind into the sails of the Arts and Crafts movement, which sought to improve the stature of decorative arts. But perhaps the most curious and remarkable twist in Morris’s legacy is his full-steam revival from the end of the twentieth century to the present. Since the 1990s, his work has been the subject of exhibitions everywhere from the V&A in London to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and many of his patterns have become icons of good English taste. What is it about Morris that resonates with us today?

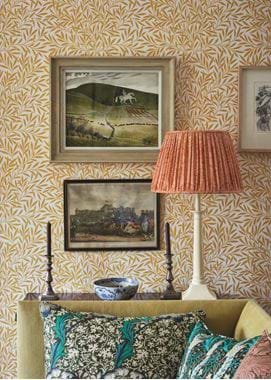

In Denham, an archivist and team of designers sit at their desks with pots of paint and Morris’s original materials, trying to answer that question. The modern incarnation of Morris & Co, owned by the Sanderson Design Group, has developed four ‘Archive’ collections in the last ten years, based on reproductions and adaptations of the classic prints, so that we can paper our dining rooms in ‘Willow’ (1874) or ‘Pimpernel’ (1876) and cover our armchairs in ‘Marigold’ (1875) like the Victorians before us. We can make door curtains in the sumptuous, blue and gold ‘Peacock and Dragon’ (1878), evocative of medieval tapestry, and cushions for our sofas (not to say shirts, trainers, and iPhone covers) from ‘Strawberry Thief’.

Morris was a reformer as well as an artist and worked against the tide in his time because he believed that unscrupulous production was damaging – to the physical quality of furniture and curtains, yes, but more broadly to the way that we live. He understood that nature is a balm, and beauty a respite. He considered the maker behind a product as well as the customer who took it home. In embracing Morris in this century, maybe we’re drawn to his humanity as much as his art.

Jo Rodgers is a journalist who lives in London and East Sussex with her husband and son. She is a contributing writer at Vogue, Conde Nast Traveller, House & Garden and Country Life. @jo_rodgers